1968 United States presidential election

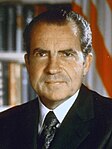

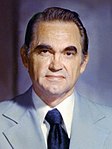

The 1968 United States presidential election was the 46th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 5, 1968. The Republican nominee, former vice president Richard Nixon, defeated both the Democratic nominee, incumbent vice president Hubert Humphrey, and the American Independent Party nominee, former Alabama governor George Wallace.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

538 members of the Electoral College 270 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 62.5%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

<imagemap>File:ElectoralCollege1968.svg|348px|center| poly 28 148 51 155 71 161 92 166 76 231 148 338 147 341 150 347 151 351 153 354 152 356 149 358 146 360 145 363 144 366 144 368 139 373 139 381 142 384 140 386 123 386 92 381 93 367 82 351 76 351 74 357 76 359 76 360 74 360 73 359 71 367 72 370 73 371 71 371 70 370 70 366 71 367 73 359 71 356 72 355 74 357 76 351 77 349 76 344 73 343 70 343 69 342 66 341 65 340 53 340 47 340 45 338 46 337 48 337 51 340 53 340 51 338 51 337 53 337 55 339 57 339 57 340 65 340 66 341 66 339 63 335 62 333 60 331 56 330 53 329 50 327 45 326 42 324 42 321 44 315 45 313 45 310 43 308 43 306 39 300 37 296 35 290 34 285 30 281 31 273 33 273 35 271 35 266 33 265 31 265 28 260 27 254 28 249 29 246 29 244 23 238 24 231 17 217 16 212 18 204 19 203 19 195 17 189 16 185 14 185 14 183 16 177 22 172 26 161 27 152 1968 United States presidential election in California poly 29 146 26 142 27 139 28 128 34 120 38 114 44 102 49 88 53 80 58 64 61 61 66 61 67 64 70 64 73 67 73 77 78 81 86 81 87 80 89 80 90 81 93 81 93 82 96 82 99 84 104 85 104 84 106 84 107 86 113 86 114 85 117 85 118 86 133 85 161 92 161 96 165 99 165 102 163 104 162 107 159 110 157 112 157 115 155 117 153 117 149 122 148 125 148 129 149 130 151 130 152 132 151 133 140 176 89 164 56 155 1968 United States presidential election in Oregon poly 161 91 161 82 174 28 116 13 93 7 92 8 93 10 94 13 90 12 88 12 86 13 85 12 84 12 85 15 87 16 87 15 88 15 88 18 89 18 90 16 91 12 94 13 95 16 94 18 94 26 94 28 95 30 94 31 93 31 92 28 90 26 90 23 92 22 92 20 91 20 89 21 88 23 88 25 85 24 80 22 74 21 72 19 69 18 64 12 62 12 61 13 61 17 60 18 60 21 61 23 61 37 61 38 62 39 62 42 65 44 65 45 61 45 60 46 60 48 62 49 63 51 62 52 61 54 59 55 59 58 60 59 60 60 61 60 61 59 65 59 65 60 68 60 68 63 72 63 73 65 75 67 75 77 80 80 84 80 87 78 92 80 98 81 99 83 106 83 109 84 114 84 115 83 119 83 119 84 136 84 1968 United States presidential election in Washington (state) poly 175 28 188 30 184 48 184 53 186 58 187 59 186 62 186 66 187 68 191 71 193 77 196 83 198 85 199 86 201 86 202 90 195 105 195 109 198 112 202 112 205 109 208 125 214 132 214 138 216 140 218 138 221 138 223 139 227 139 228 138 233 139 235 140 237 140 239 137 241 137 242 141 244 141 235 194 188 186 141 177 152 135 154 131 153 129 150 129 150 125 152 122 155 118 158 117 158 114 164 106 167 103 167 98 163 96 163 83 166 67 170 47 1968 United States presidential election in Idaho poly 148 336 77 231 94 167 136 177 187 187 163 313 161 316 159 313 153 311 151 313 150 335 1968 United States presidential election in Nevada poly 168 295 189 188 235 196 231 220 264 224 262 245 253 309 1968 United States presidential election in Utah poly 235 434 197 429 135 391 135 390 137 388 143 387 144 383 143 381 140 380 140 374 146 370 146 364 147 360 154 356 154 353 152 351 152 345 149 342 149 339 151 337 152 316 154 313 157 315 160 318 163 318 165 314 167 296 206 303 224 307 252 311 244 374 1968 United States presidential election in Arizona poly 189 31 252 43 304 50 361 56 358 102 354 142 302 137 246 129 245 140 243 139 242 134 239 134 236 138 234 138 232 137 226 137 225 137 223 137 221 136 217 137 215 137 215 131 210 124 207 108 205 107 202 110 199 110 197 109 197 105 204 87 203 85 200 85 196 79 195 75 193 72 191 69 187 67 187 62 188 58 185 53 1968 United States presidential election in Montana poly 233 218 248 131 298 138 354 144 350 194 346 230 1968 United States presidential election in Wyoming poly 254 309 261 259 265 223 324 230 380 235 374 321 316 316 1968 United States presidential election in Colorado poly 237 433 249 350 254 311 331 320 357 322 356 331 355 332 348 429 320 427 281 424 281 430 264 428 253 426 252 435 1968 United States presidential election in New Mexico poly 357 121 361 88 363 57 385 59 424 61 460 61 463 65 462 82 463 84 464 88 466 91 467 104 468 107 468 114 470 118 471 127 417 126 1968 United States presidential election in North Dakota poly 353 187 357 124 411 127 471 128 471 132 467 134 467 138 473 142 473 180 470 182 470 187 473 190 472 193 469 199 466 197 461 196 458 195 452 195 449 196 441 190 423 191 384 188 1968 United States presidential election in South Dakota poly 489 257 486 253 485 249 482 244 482 234 480 231 480 225 477 222 475 212 473 205 470 204 469 201 458 196 451 197 448 199 440 192 418 192 352 188 349 231 382 234 380 256 438 257 445 258 1968 United States presidential election in Nebraska poly 376 321 380 257 420 259 491 260 493 263 497 263 498 265 496 267 496 271 502 279 504 292 503 325 436 324 1968 United States presidential election in Kansas poly 358 332 359 322 404 324 446 326 503 326 503 334 504 341 506 363 507 400 505 399 500 397 497 394 495 394 492 396 490 395 488 394 486 394 484 396 481 395 479 395 479 397 476 399 473 398 469 396 465 396 465 394 463 394 463 396 461 398 459 398 455 397 454 394 449 393 448 395 445 395 444 392 442 391 442 389 437 389 437 390 435 390 433 389 432 388 428 388 427 387 423 387 423 384 421 382 419 383 417 383 417 382 414 383 410 378 410 359 411 343 412 334 1968 United States presidential election in Oklahoma poly 350 431 353 376 357 334 410 336 408 365 408 379 414 385 418 384 422 384 421 387 424 388 428 390 432 390 436 392 437 391 440 390 445 397 448 397 450 395 452 395 455 398 460 400 464 396 469 398 475 400 477 400 479 398 482 397 485 398 487 396 489 397 493 397 495 396 503 400 506 401 510 404 512 403 515 403 516 432 516 433 517 438 519 441 520 446 524 451 525 458 525 463 522 467 522 468 523 472 523 475 522 481 521 483 521 487 514 489 509 492 505 493 503 497 499 499 486 510 477 513 467 520 463 521 458 527 454 527 453 529 455 531 451 545 451 551 453 559 454 566 455 569 457 567 456 559 454 554 454 552 453 550 453 544 455 535 460 527 464 522 465 522 465 523 461 528 458 532 455 535 453 545 454 545 454 550 455 551 455 556 457 558 458 561 458 567 457 567 453 571 450 571 446 568 442 567 436 567 432 563 426 562 419 559 417 554 417 551 415 547 413 546 413 540 412 539 412 536 413 535 410 532 407 530 402 521 396 517 396 514 391 502 391 499 389 497 389 495 380 488 380 486 378 483 372 483 371 482 362 482 361 481 358 480 355 481 350 485 349 490 345 493 345 495 342 498 340 498 338 496 332 494 329 490 325 489 317 480 315 476 315 466 312 463 312 460 308 455 304 454 295 444 294 440 288 438 288 435 285 432 283 430 283 426 316 429 1968 United States presidential election in Texas poly 475 180 475 141 469 137 469 135 472 132 472 118 470 113 469 106 469 101 468 99 468 88 464 82 464 68 465 65 463 63 463 61 493 61 494 53 498 55 498 62 501 67 505 67 507 69 512 69 513 71 517 71 521 68 528 71 535 74 538 74 539 73 540 76 544 78 546 80 551 80 556 76 557 76 559 79 561 79 561 78 570 78 571 81 575 79 577 80 573 83 569 84 563 87 559 89 552 95 552 98 549 100 537 110 536 123 528 130 528 134 531 138 531 141 529 143 529 155 533 158 536 158 539 161 541 161 549 169 551 170 555 174 555 179 512 180 1968 United States presidential election in Minnesota poly 486 245 484 243 483 236 483 233 481 231 481 225 479 222 478 216 475 210 475 205 473 202 472 201 472 197 473 195 474 189 471 186 471 182 503 182 556 181 556 183 559 186 557 188 557 194 560 198 565 199 566 201 566 203 570 205 570 207 575 211 574 217 572 219 572 221 570 223 564 224 561 227 561 232 563 233 563 236 561 237 561 242 557 244 557 247 556 248 553 245 553 243 515 244 1968 United States presidential election in Iowa poly 505 335 505 284 504 281 504 277 497 270 497 268 499 266 499 264 498 262 493 261 487 252 486 247 551 245 555 249 555 257 557 261 557 264 566 272 570 275 570 280 572 281 578 281 580 283 580 286 578 288 576 296 585 305 589 305 591 307 591 310 593 312 593 314 593 316 594 320 596 322 599 323 600 327 593 333 593 339 591 340 592 343 588 345 584 344 583 342 587 339 586 335 584 333 541 335 1968 United States presidential election in Missouri poly 569 412 517 412 517 404 514 401 511 402 509 402 508 401 508 361 507 356 507 342 505 338 505 337 538 336 584 335 585 338 584 340 581 342 580 344 580 346 590 346 590 348 589 349 589 353 584 356 584 359 585 360 584 365 582 366 582 369 578 372 578 374 577 376 577 378 574 382 571 385 571 387 572 387 572 389 568 391 568 395 567 397 567 399 568 401 567 402 567 404 569 406 1968 United States presidential election in Arkansas poly 522 488 523 483 524 481 524 473 525 472 525 471 524 470 524 468 526 465 527 455 526 454 526 451 521 446 521 441 518 435 517 414 541 414 568 413 568 419 569 420 570 425 571 426 571 429 570 430 570 433 568 437 567 441 565 442 565 444 562 447 562 457 565 458 597 457 596 464 600 468 602 474 600 475 599 478 600 480 603 480 603 479 605 475 606 475 607 477 607 479 608 480 608 481 606 482 604 482 603 484 602 484 602 487 604 490 608 490 615 493 615 495 613 496 608 495 605 493 601 493 599 489 595 490 595 493 596 494 594 497 591 498 590 499 590 498 592 497 591 494 589 494 586 495 585 497 582 499 578 499 571 495 573 492 571 489 567 490 565 485 560 485 558 484 556 484 555 486 555 488 560 488 562 489 562 490 559 490 558 489 554 489 553 490 547 490 542 487 535 485 530 485 524 486 1968 United States presidential election in Louisiana poly 538 123 538 111 541 109 544 111 545 111 551 109 557 105 559 104 561 105 559 107 558 111 558 112 560 112 561 111 563 111 564 113 567 113 571 118 574 118 599 124 601 124 604 127 607 128 608 137 612 140 607 146 606 152 607 154 611 150 611 148 620 136 620 137 620 140 614 152 613 158 614 159 614 162 612 163 612 168 613 169 613 174 612 175 611 179 610 180 610 182 611 184 611 189 613 193 613 197 598 198 566 200 565 198 562 197 559 194 559 188 561 186 557 183 557 174 553 169 550 168 544 161 542 160 540 160 538 156 534 156 532 154 531 143 533 140 533 138 530 134 530 130 535 126 1968 United States presidential election in Wisconsin poly 568 201 590 201 613 199 613 204 617 209 618 216 623 265 622 267 622 273 624 276 625 282 622 284 622 287 617 293 617 304 614 306 615 307 617 309 614 311 612 311 610 313 611 316 612 317 610 319 609 317 606 317 605 316 600 319 598 321 595 319 594 315 595 314 595 310 592 308 592 305 590 304 585 304 578 295 578 292 580 287 582 284 582 281 578 280 572 281 571 278 571 274 558 263 558 259 556 257 556 251 559 248 559 245 562 243 562 239 565 237 565 233 562 230 562 229 564 226 570 225 573 222 573 219 576 216 576 211 568 202 1968 United States presidential election in Illinois poly 632 211 685 206 686 203 690 200 690 194 692 193 693 188 694 186 696 187 698 187 698 177 692 160 688 155 682 158 682 161 679 164 678 167 675 167 672 165 672 161 674 159 677 156 676 153 679 151 679 140 676 137 675 135 678 134 674 129 670 129 662 124 658 125 654 122 654 118 655 116 664 115 666 116 671 117 673 114 670 112 667 113 667 114 669 114 668 116 666 116 661 112 661 106 660 104 659 105 651 107 647 107 647 101 646 100 639 104 632 104 629 105 624 110 621 111 619 110 618 109 617 109 616 110 611 110 609 107 609 105 606 103 601 102 600 101 599 101 596 104 594 104 594 102 597 98 597 96 600 94 601 92 603 91 605 91 605 90 604 89 602 89 598 90 595 92 591 97 589 98 588 100 588 101 585 102 583 103 582 105 579 106 575 106 574 108 569 110 569 112 570 114 572 116 575 116 588 119 591 120 595 121 597 122 600 122 602 123 603 123 604 125 607 126 609 127 609 133 610 137 612 138 613 136 615 131 615 128 617 126 618 124 620 124 621 125 622 124 624 123 626 123 627 124 628 124 629 122 630 119 639 118 641 116 648 116 652 117 654 117 654 122 652 123 649 125 649 128 652 129 653 130 653 131 650 132 646 133 647 137 647 142 645 144 642 145 642 140 644 137 644 135 642 135 641 137 641 140 636 142 636 147 634 148 634 156 632 159 632 166 633 167 633 169 632 169 632 173 636 180 639 188 639 195 638 198 638 201 635 205 635 209 1968 United States presidential election in Michigan poly 662 210 631 213 626 216 624 217 620 216 623 243 624 274 626 276 626 283 623 288 623 289 620 294 619 300 620 300 626 298 632 298 633 300 634 300 635 297 638 296 640 296 641 298 642 298 642 295 647 292 650 294 653 294 653 289 661 281 661 277 665 277 670 274 669 272 666 240 1968 United States presidential election in Indiana poly 670 267 664 211 688 208 690 211 697 210 699 213 704 213 707 211 714 210 722 201 731 196 736 224 734 225 734 230 735 230 734 246 728 253 724 253 720 258 720 263 719 264 718 263 716 263 714 266 714 273 713 274 713 277 709 277 705 274 705 272 703 271 700 272 698 274 697 274 696 273 691 273 690 274 689 274 687 272 683 273 682 272 681 269 677 266 1968 United States presidential election in Ohio poly 700 319 709 314 709 311 721 299 712 290 712 288 708 285 708 277 704 276 704 274 703 273 698 277 696 277 696 275 692 275 691 276 687 276 687 274 682 274 680 273 679 270 677 268 675 268 675 269 670 269 670 271 671 272 671 275 665 279 662 279 662 283 654 290 654 295 649 295 647 294 644 296 644 299 641 300 640 298 637 298 634 302 633 302 630 300 622 300 619 302 617 306 617 308 618 309 618 310 612 313 612 316 613 316 613 319 613 320 609 320 606 318 604 318 600 320 601 322 602 324 602 326 601 327 601 329 597 332 620 330 620 327 1968 United States presidential election in Kentucky poly 586 366 587 360 586 359 586 357 590 355 595 334 621 332 621 328 727 318 729 316 730 316 730 320 727 323 726 327 724 326 721 327 720 330 718 330 716 329 711 334 711 336 708 337 701 343 699 343 697 345 694 346 694 349 689 352 688 357 637 362 1968 United States presidential election in Tennessee poly 603 473 607 468 610 469 614 468 614 466 617 466 619 468 624 468 624 459 619 435 621 365 602 367 584 367 584 369 579 374 579 381 577 382 573 386 573 390 570 392 569 398 570 400 570 402 569 404 571 406 571 410 570 412 570 420 572 421 572 425 574 426 574 428 572 429 573 434 570 437 568 442 564 447 564 457 598 455 599 456 599 460 598 461 598 464 602 467 1968 United States presidential election in Mississippi poly 666 361 622 365 622 438 626 466 629 467 631 463 631 459 635 460 638 467 637 468 636 468 636 469 638 469 642 467 642 460 638 456 638 451 659 448 686 446 686 445 684 443 683 433 683 424 685 421 685 419 683 418 683 414 679 411 670 376 667 369 1968 United States presidential election in Alabama poly 710 356 668 361 668 367 673 377 681 411 684 413 684 417 686 417 686 421 685 425 684 431 686 435 686 440 685 441 685 443 687 444 688 448 691 452 742 450 742 453 743 453 744 448 743 445 743 444 745 443 748 444 756 444 754 440 754 437 758 425 758 421 761 416 760 414 758 415 755 413 755 409 752 406 748 403 747 399 744 394 740 392 737 388 733 384 730 381 723 378 717 367 712 367 707 363 707 359 1968 United States presidential election in Georgia poly 639 452 674 448 686 448 691 454 740 451 741 454 746 455 746 448 745 447 745 445 755 446 761 462 768 475 774 483 780 489 779 491 779 494 781 501 785 504 787 510 792 518 795 523 797 547 795 548 795 556 797 555 797 553 798 553 797 556 796 558 795 562 792 566 785 572 782 574 778 574 775 573 772 576 769 577 768 579 769 579 771 577 773 577 774 576 777 576 778 574 782 574 782 572 788 569 792 564 794 561 796 557 796 555 795 556 795 557 792 560 789 561 786 561 783 564 781 563 780 563 780 559 779 559 779 557 777 554 776 551 773 550 772 548 768 548 766 549 764 547 764 542 762 540 760 537 758 537 757 538 755 538 754 534 750 529 749 526 745 521 742 519 742 517 747 511 747 508 742 507 740 507 740 509 742 509 742 511 742 514 740 512 740 511 739 509 738 507 738 501 739 499 739 488 736 485 736 483 734 481 729 481 727 479 725 476 722 475 722 472 719 472 717 468 714 467 713 466 711 465 709 464 705 464 704 465 702 465 702 468 703 469 699 469 697 471 694 473 688 474 686 475 685 473 682 470 671 465 665 463 659 463 651 464 644 467 643 459 639 456 1968 United States presidential election in Florida poly 708 361 708 359 711 357 711 355 716 354 728 348 750 347 754 352 770 350 784 357 795 366 791 371 788 377 788 383 785 387 782 388 782 390 777 395 777 397 772 402 767 402 767 404 768 405 768 406 763 412 760 413 757 413 756 410 756 407 753 405 750 403 749 399 747 396 747 394 744 392 742 391 739 387 727 377 724 376 721 372 720 369 718 367 717 365 712 365 1968 United States presidential election in South Carolina poly 732 316 741 315 771 312 831 299 836 308 839 312 842 314 844 317 844 326 844 327 842 327 838 331 836 331 841 327 843 326 843 318 841 314 841 313 840 313 840 314 838 314 838 320 835 321 833 326 830 327 825 326 825 328 826 328 827 329 827 331 826 333 826 335 827 336 829 336 831 337 833 334 834 335 833 338 830 340 830 342 825 342 819 344 812 350 809 354 807 360 807 364 802 364 796 365 787 357 773 349 766 349 754 351 751 346 731 346 726 347 715 352 710 354 694 357 690 357 690 354 692 352 695 351 695 347 701 344 703 344 710 338 713 337 713 335 716 332 721 332 723 328 727 328 728 326 729 323 732 321 1968 United States presidential election in North Carolina poly 704 319 711 314 711 311 722 299 727 304 732 304 734 302 737 303 742 302 743 297 745 299 748 296 753 294 753 288 756 281 759 275 759 269 763 272 767 271 768 269 768 263 772 262 772 260 777 256 777 254 778 253 778 247 789 251 789 248 794 254 794 262 798 260 798 264 803 266 809 268 811 268 814 270 817 270 818 271 818 277 820 278 820 280 820 281 817 281 817 284 820 285 822 287 822 289 820 291 820 293 824 293 827 292 827 286 826 282 826 277 828 273 829 267 834 265 834 268 831 271 831 283 829 286 827 285 827 292 831 298 770 310 728 315 728 316 1968 United States presidential election in Virginia poly 741 244 737 226 736 226 736 246 731 252 728 255 726 255 722 260 721 262 722 263 722 265 720 266 718 265 716 267 716 274 714 275 714 278 710 279 710 285 713 286 714 288 714 290 721 297 723 297 726 302 732 302 734 300 737 301 741 300 742 295 745 296 747 294 751 294 752 292 752 290 751 288 757 274 758 267 761 267 763 269 765 269 767 261 770 260 770 258 775 254 777 251 777 245 779 245 787 249 787 245 784 242 781 240 780 240 775 244 770 244 767 248 765 248 760 254 758 254 756 242 1968 United States presidential election in West Virginia poly 795 260 800 257 807 260 806 253 810 248 803 248 800 241 797 248 790 248 796 254 1968 United States presidential election in the District of Columbia poly 758 242 759 252 764 247 766 247 770 242 774 242 778 239 781 239 784 240 789 244 791 245 793 247 796 247 800 239 804 247 811 247 811 248 807 253 808 261 801 258 800 259 800 263 803 264 810 265 814 267 816 267 815 264 811 257 810 251 811 249 811 247 810 244 811 240 815 236 816 237 816 239 813 241 813 243 816 245 816 250 814 251 814 255 816 253 817 255 815 256 815 260 819 263 821 263 821 265 822 270 823 270 823 266 821 264 821 263 822 262 824 263 826 266 828 266 830 265 835 264 836 262 837 256 834 256 832 257 824 257 822 245 819 236 817 230 1968 United States presidential election in Maryland poly 822 227 819 229 819 232 820 234 821 238 823 240 823 245 824 247 825 252 826 256 836 254 836 251 835 250 834 248 830 246 826 238 823 236 822 231 1968 United States presidential election in Delaware poly 743 186 738 192 733 194 734 201 742 242 772 237 819 228 822 225 825 224 828 220 832 216 826 212 825 210 821 210 821 206 824 203 824 201 822 200 823 197 824 196 824 192 827 189 823 189 821 187 820 182 815 181 814 179 773 188 744 193 1968 United States presidential election in Pennsylvania poly 842 195 832 192 828 190 826 192 826 197 824 198 824 200 825 201 825 204 823 206 824 208 826 209 827 211 833 215 833 218 830 220 826 226 824 227 824 232 829 236 833 238 836 238 836 244 839 240 839 235 841 235 846 224 845 211 843 207 840 208 840 206 842 204 1968 United States presidential election in New Jersey poly 830 107 818 111 811 112 806 114 797 126 794 131 790 134 790 138 794 138 794 141 793 142 793 144 795 145 795 148 793 150 790 150 789 153 786 156 779 158 776 160 772 160 771 158 763 158 751 163 751 165 752 165 753 168 755 169 756 172 756 175 753 177 753 179 745 186 745 192 816 177 817 180 821 180 822 182 822 185 825 188 828 188 833 190 841 193 844 194 844 204 850 203 857 200 865 194 871 189 868 187 864 191 857 195 854 195 851 194 847 198 845 200 845 198 846 196 846 194 844 193 844 191 845 190 845 181 842 168 843 151 840 140 839 138 836 137 836 136 837 135 837 133 834 128 834 122 834 117 1968 United States presidential election in New York poly 869 166 861 168 845 171 845 176 847 180 847 195 857 186 861 184 868 182 872 180 871 172 1968 United States presidential election in Connecticut poly 877 164 872 165 873 170 874 180 877 179 880 175 883 175 884 173 1968 United States presidential election in Rhode Island poly 854 152 855 144 854 142 854 132 855 130 855 120 854 119 854 116 856 116 860 112 860 107 858 105 858 99 844 104 832 107 833 113 835 116 836 124 835 125 835 128 838 131 838 134 839 137 841 137 843 146 844 148 844 154 1968 United States presidential election in Vermont poly 863 93 860 93 859 94 860 105 862 108 862 112 855 118 855 119 856 119 856 151 876 146 877 143 882 141 882 139 880 137 880 134 877 133 875 133 873 123 1968 United States presidential election in New Hampshire poly 868 92 865 92 869 106 875 125 877 132 879 132 881 134 881 136 883 137 883 133 884 133 884 126 886 125 886 124 885 123 885 121 886 120 887 118 889 118 890 120 891 120 894 117 896 116 897 113 900 113 901 111 901 104 900 102 901 100 903 102 905 103 905 105 905 106 903 106 903 107 903 109 904 110 906 110 906 109 904 107 904 106 905 106 907 106 908 104 908 102 907 102 907 100 910 97 913 97 914 99 911 99 909 100 909 102 910 103 911 103 912 101 913 100 913 99 915 99 919 94 923 91 924 90 926 89 927 85 927 82 924 78 924 77 922 77 921 79 919 79 917 77 916 71 909 71 901 41 892 37 886 42 885 44 882 43 880 40 879 39 878 39 876 44 874 52 872 56 872 65 870 68 870 73 872 74 872 77 870 80 868 84 1968 United States presidential election in Maine poly 844 169 844 155 857 153 876 148 877 146 879 144 881 144 883 146 883 149 881 150 881 154 883 158 884 156 886 156 893 165 896 165 900 163 900 161 899 158 895 158 895 157 898 157 900 159 902 163 902 164 901 165 897 166 894 168 893 169 892 171 892 172 894 172 895 173 902 173 903 172 904 172 904 174 902 174 902 173 896 173 895 174 893 174 893 175 891 175 891 174 892 172 889 174 889 173 891 171 891 168 890 167 887 168 887 173 885 173 882 167 877 162 859 166 1968 United States presidential election in Massachusetts poly 215 493 215 550 250 592 354 592 354 546 301 493 1968 United States presidential election in Hawaii poly 160 539 160 454 154 450 152 449 149 451 145 449 142 448 140 449 134 445 128 445 125 443 125 439 122 439 119 440 119 438 115 434 113 434 111 437 104 437 99 439 96 438 92 440 92 443 88 447 78 447 77 447 76 449 78 453 82 458 82 462 83 465 85 465 85 468 87 472 87 475 83 475 78 473 77 470 79 469 78 467 74 467 72 468 72 469 70 468 61 468 61 469 62 471 65 474 65 477 64 478 64 481 68 485 74 485 77 487 80 487 80 486 84 486 85 488 83 489 83 495 80 499 76 498 76 497 71 499 68 497 65 496 63 498 63 501 55 506 54 512 57 513 56 516 54 517 55 520 57 522 58 526 64 527 65 526 67 527 67 533 64 533 65 537 64 539 66 540 67 539 72 539 72 541 74 540 75 541 75 546 76 546 77 543 78 542 80 542 80 545 85 543 85 545 81 550 80 555 75 557 74 559 74 561 68 561 63 563 62 565 58 564 53 565 49 567 45 569 42 568 39 568 37 569 37 571 38 572 40 571 43 570 45 571 47 571 50 570 53 569 55 568 58 568 58 569 62 568 65 567 66 568 67 568 68 567 72 567 73 568 75 566 73 565 74 564 78 561 83 560 94 555 103 548 100 545 100 543 104 539 106 539 108 537 108 536 114 530 116 529 117 527 122 527 122 529 123 531 120 532 119 531 116 532 114 535 112 538 112 539 111 541 114 541 114 543 110 543 110 545 115 545 122 539 124 539 125 541 126 541 127 540 129 540 129 543 130 543 134 538 134 537 131 540 130 539 132 536 131 535 129 537 129 533 132 531 136 531 138 535 139 536 141 538 143 538 146 541 156 541 162 544 166 543 167 541 168 542 168 545 167 546 167 547 170 548 176 552 178 554 181 556 184 556 184 557 183 559 183 561 185 563 186 568 188 569 193 575 193 569 195 571 195 575 196 576 197 573 199 574 199 578 201 580 200 581 199 581 200 583 201 582 202 585 205 590 205 589 204 586 204 585 207 586 208 587 208 582 207 581 207 579 209 580 212 582 214 585 216 586 218 582 218 578 217 574 209 571 206 570 206 568 202 562 198 556 197 554 192 551 192 549 189 549 189 545 186 544 182 546 182 549 177 552 177 549 170 543 170 540 169 539 167 539 166 540 162 540 1968 United States presidential election in Alaska rect 865 306 928 326 1968 United States presidential election in the District of Columbia rect 883 288 970 306 1968 United States presidential election in Maryland rect 892 264 949 285 1968 United States presidential election in Delaware rect 899 244 971 261 1968 United States presidential election in New Jersey rect 919 211 976 229 1968 United States presidential election in Connecticut rect 926 183 979 200 1968 United States presidential election in Rhode Island rect 928 148 1012 165 1968 United States presidential election in Massachusetts rect 790 62 850 82 1968 United States presidential election in Vermont rect 801 42 868 58 1968 United States presidential election in New Hampshire </imagemap>Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Nixon/Agnew, blue denotes those won by Humphrey/Muskie, and orange denotes those won by Wallace/LeMay, including a North Carolina faithless elector. Numbers indicate electoral votes cast by each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Incumbent president Lyndon B. Johnson had been the early front-runner for the Democratic Party's nomination, but he withdrew from the race after only narrowly winning the New Hampshire primary. Eugene McCarthy, Robert F. Kennedy and Humphrey emerged as the three major candidates in the Democratic primaries until Kennedy was assassinated. His death after midnight on June 6, 1968, continued a streak of high-profile assassinations in the 1960s. Humphrey edged out anti-Vietnam war candidate McCarthy to win the Democratic nomination, sparking numerous anti-war protests. Nixon entered the Republican primaries as the front-runner, defeating liberal New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, conservative governor of California Ronald Reagan, and other candidates to win his party's nomination. Alabama's Democratic former governor, George Wallace, ran on the American Independent Party ticket, campaigning in favor of racial segregation on the basis of "states' rights". The election year was tumultuous and chaotic. It was marked by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in early April, and the subsequent 54 days of riots across the nation, by the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in early June, and by widespread opposition to the Vietnam War across university campuses. Vice President Hubert Humphrey won and secured the Democratic nomination, with Humphrey promising to continue Johnson's war on poverty and to support the civil rights movement.

The support of civil rights by the Johnson administration hurt Humphrey's image in the South, leading the prominent Democratic governor of Alabama, George Wallace, to mount a third-party challenge to defend racial segregation on the basis of "states' rights". Wallace led his American Independent Party attracting socially conservative voters throughout the South, and encroaching further support from white working-class voters in the Industrial North and Midwest who were attracted to Wallace's economic populism and anti-establishment rhetoric. In doing so, Wallace split the New Deal Coalition, winning over Southern Democrats, as well as former Goldwater supporters who preferred Wallace to Nixon. Nixon chose to take advantage of Democratic infighting by running a more centrist platform aimed at attracting moderate voters as part of his "silent majority" who were alienated by both the liberal agenda that was advocated by Hubert Humphrey and by the ultra-conservative viewpoints of George Wallace on race and civil rights. However, Nixon also employed coded language to combat Wallace in the Upper South, where the electorate was less extreme on the segregation issue. Nixon sought to restore law and order to the nation's cities and provide new leadership in the Vietnam War.

During most of the campaign, Humphrey trailed Nixon significantly in polls taken from late August to early October, with some polls predicting a margin of victory of as high as 16% as late as August. In the final month of the campaign, however, Humphrey managed to narrow Nixon's lead after Wallace's candidacy collapsed and Johnson suspended bombing in the Vietnam War to appease the anti-war movement; the election was considered a tossup by election day. Nixon managed to secure a close victory in the popular vote on election day, with just over 500,000 votes (0.7%) separating him and Humphrey. In the electoral college, however, Nixon's victory was much larger; he carried the tipping point state of Ohio by over 90,000 votes (2.3%), and his overall margin of victory in the electoral college was 110 votes. This election was the first presidential election after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which began restoring voting rights to Black Americans in the South, where most had been disenfranchised since the early 20th century.[2]

Nixon also became the first non-incumbent vice president to be elected president, something that would not happen again until 2020, when Joe Biden was elected president.[3] This was the last election until 2024 in which the incumbent president was eligible to run again but was not the eventual nominee of their party. Humphrey was the last nominee who did not participate in the primaries as a presidential candidate until Kamala Harris, also in 2024. Nixon's victory also commenced the Republican Party's lock on certain Western states that would vote for them in every election until 1992, allowing them to win the presidency in five of the six presidential elections that took place in that period. Additionally, this was the last election until 1988 in which the incumbent president was not on the ballot; and one of only two elections in history where a presidential candidate lost despite carrying both New-York and Texas, the other one being 1876, and the only time in which a candidate won both states yet lost the popular vote.

Background

In the election of 1964, incumbent Democratic U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson won the largest popular vote landslide in U.S. presidential election history over Republican U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater. During the presidential term that followed, Johnson was able to achieve many political successes, including passage of his Great Society domestic programs (including "War on Poverty" legislation), landmark civil rights legislation, and the continued exploration of space. Despite these significant achievements, Johnson's popular support would be short-lived. Even as Johnson scored legislative victories, the country endured large-scale race riots in the streets of its larger cities, along with a generational revolt of young people and violent debates over foreign policy. The emergence of the hippie counter-culture, the rise of New Left activism, and the emergence of the Black Power movement exacerbated social and cultural clashes between classes, generations, and races. Adding to the national crisis, on April 4, 1968, civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, igniting riots of grief and anger across the country. In Washington, D.C., rioting took place within a few blocks of the White House, and the government stationed soldiers with machine guns on the Capitol steps to protect it.[4][5]

The Vietnam War was the primary reason for the precipitous decline of President Johnson's popularity. He had escalated U.S. commitment so by late 1967 over 500,000 American soldiers were fighting in Vietnam. Draftees made up 42 percent of the military in Vietnam, but suffered 58% of the casualties, as nearly 1000 Americans a month were killed, and many more were injured.[6] Resistance to the war rose as success seemed ever out of reach. The national news media began to focus on the high costs and ambiguous results of escalation, despite Johnson's repeated efforts to downplay the seriousness of the situation.

In early January 1968, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara said the war would be winding down, claiming that the North Vietnamese were losing their will to fight. But, shortly thereafter, the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive, in which they and Communist forces of Vietcong undertook simultaneous attacks on all government strongholds across South Vietnam. Though the uprising ended in a U.S. military victory, the scale of the Tet offensive led many Americans to question whether the war could be "won", or was worth the costs to the U.S. In addition, voters began to mistrust the government's assessment and reporting of the war effort. The Pentagon called for sending several hundred thousand more soldiers to Vietnam, while Johnson's approval ratings fell below 35%. The Secret Service refused to let the president visit American colleges and universities, and prevented him from appearing at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, because it could not guarantee his safety.[7]

Republican Party nomination

| Richard Nixon | Spiro Agnew | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36th Vice President of the United States (1953–1961) |

55th Governor of Maryland (1967–1969) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other major candidates

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks, were listed in publicly published national polls, or ran a campaign that extended beyond their flying home delegation in the case of favorite sons.

Nixon received 1,679,443 votes in the primaries.

| Candidates in this section are sorted by date of withdrawal from the nomination race | |||

| Ronald Reagan | Nelson Rockefeller | Harold Stassen | George W. Romney |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governor of California (1967–1975) |

Governor of New York (1959–1973) |

Former president of the University of Pennsylvania (1948–1953) |

Governor of Michigan (1963–1969) |

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | |

| Lost nomination: August 8, 1968 1,696,632 votes |

Lost nomination: August 8, 1968 164,340 votes |

Lost nomination: August 8, 1968 31,665 votes |

Withdrew: February 28, 1968 4,447 votes |

Primaries

The front-runner for the Republican nomination was former Vice President Richard Nixon, who formally began campaigning in January 1968.[8] Nixon had worked behind the scenes and was instrumental in Republican gains in Congress and governorships in the 1966 midterm elections. Thus, the party machinery and many of the new congressmen and governors supported him. Still, there was caution in the Republican ranks over Nixon, who had lost the 1960 election to John F. Kennedy and then lost the 1962 California gubernatorial election. Some hoped a more "electable" candidate would emerge. The story of the 1968 Republican primary campaign and nomination may be seen as one Nixon opponent after another entering the race and then dropping out. Nixon was the front runner throughout the contest because of his superior organization, and he easily defeated the rest of the field.

Nixon's first challenger was Michigan Governor George W. Romney. A Gallup poll in mid-1967 showed Nixon with 39%, followed by Romney with 25%. After a fact-finding trip to Vietnam, Romney told Detroit talk show host Lou Gordon that he had been "brainwashed" by the military and the diplomatic corps into supporting the Vietnam War; the remark led to weeks of ridicule in the national news media. Turning against American involvement in Vietnam, Romney planned to run as the anti-war Republican version of Eugene McCarthy.[9] But, following his "brainwashing" comment, Romney's support faded steadily; with polls showing him far behind Nixon, he withdrew from the race on February 28, 1968.[10]

Senator Charles Percy was considered another potential threat to Nixon, and had planned on waging an active campaign after securing a role as Illinois's favorite son. Later, however, Percy declined to have his name listed on the ballot for the Illinois presidential primary, as he no longer sought the presidential nomination.[11]

Nixon won a resounding victory in the important New Hampshire primary on March 12, with 78% of the vote. Anti-war Republicans wrote in the name of New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, the de facto leader of the Republican Party's liberal wing, who received 11% of the vote and became Nixon's new challenger. Rockefeller had not originally intended to run, having discounted a campaign for the nomination in 1965, and planned to make United States Senator Jacob Javits, the favorite son, either in preparation of a presidential campaign or to secure him the second spot on the ticket. As Rockefeller warmed to the idea of entering the race, Javits shifted his effort to seeking a third term in the Senate.[12] Nixon led Rockefeller in the polls throughout the primary campaign—though Rockefeller defeated Nixon and Governor John Volpe in the Massachusetts primary on April 30, he otherwise fared poorly in state primaries and conventions. He had declared too late to get his name placed on state primary ballots.

By early spring, California Governor Ronald Reagan, a leader of the Republican Party's conservative wing, had become Nixon's chief rival. In the Nebraska primary on May 14, Nixon won with 70% of the vote to 21% for Reagan and 5% for Rockefeller. While this was a wide margin for Nixon, Reagan remained Nixon's leading challenger. Nixon won the next primary of importance, Oregon, on May 15 with 65% of the vote, and won all the following primaries except for California (June 4), where only Reagan appeared on the ballot. Reagan's victory in California gave him a plurality of the nationwide primary vote, but his poor showing in most other state primaries left him far behind Nixon in the delegate count.

Total popular vote:[clarification needed]

|

|

Republican Convention

As the 1968 Republican National Convention opened on August 5 in Miami Beach, Florida, the Associated Press estimated that Nixon had 656 delegate votes – 11 short of the number he needed to win the nomination. Reagan and Rockefeller were his only remaining opponents and they planned to unite their forces in a "stop-Nixon" movement.

Because Goldwater had done well in the Deep South, delegates to the 1968 Republican National Convention included more Southern conservatives than in past conventions. There seemed potential for the conservative Reagan to be nominated if no victor emerged on the first ballot. Nixon narrowly secured the nomination on the first ballot, with the aid of South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had switched parties in 1964.[13][page needed] He selected dark horse Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew as his running mate, a choice which Nixon believed would unite the party, appealing to both Northern moderates and Southerners disaffected with the Democrats.[14] Nixon's first choice for running mate was reportedly his longtime friend and ally Robert Finch, who was the Lieutenant Governor of California at the time. Finch declined that offer, but later accepted an appointment as the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in Nixon's administration. With Vietnam a key issue, Nixon had strongly considered tapping his 1960 running mate, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., a former U.S. senator, ambassador to the UN, and ambassador twice to South Vietnam.

| President | (before switches) | (after switches) | Vice President | Vice-Presidential votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richard Nixon | 692 | 1238 | Spiro Agnew | 1119 |

| Nelson Rockefeller | 277 | 93 | George W. Romney | 186 |

| Ronald Reagan | 182 | 2 | John V. Lindsay | 10 |

| Ohio governor James A. Rhodes | 55 | — | Massachusetts senator Edward Brooke | 1 |

| Michigan governor George W. Romney | 50 | — | James A. Rhodes | 1 |

| New Jersey senator Clifford Case | 22 | — | not voting | 16 |

| Kansas senator Frank Carlson | 20 | — | — | |

| Arkansas governor Winthrop Rockefeller | 18 | — | — | |

| Hawaii senator Hiram Fong | 14 | — | — | |

| Harold Stassen | 2 | — | — | |

| New York City mayor John V. Lindsay | 1 | — | — |

As of the 2020 presidential election, 1968 was the last time that two siblings (Nelson and Winthrop Rockefeller) ran against each other in a presidential primary.

Democratic Party nomination

| Hubert Humphrey | Edmund Muskie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38th Vice President of the United States (1965–1969) |

U.S. Senator from Maine (1959–1980) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other major candidates

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks, were listed in publicly published national polls, or ran a campaign that extended beyond their home delegation in the case of favorite sons.

Humphrey received 166,463 votes in the primaries.

| Candidates in this section are sorted by date of withdrawal from the nomination race | ||||||||

| Eugene McCarthy | George McGovern | Channing E. Phillips | Lester Maddox | Robert F. Kennedy | Lyndon B. Johnson | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. senator from Minnesota (1959–1971) |

U.S. senator from South Dakota (1963–1981) |

Reverend at Lincoln Temple from Washington, D.C. |

Governor of Georgia (1967–1971) |

U.S. senator from New York (1965–1968) |

36th President of the United States (1963–1969) | |||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | ||||

| Lost nomination: August 29, 1968 2,914,933 votes |

Lost nomination: August 29, 1968 0 votes |

Lost nomination: August 29, 1968 0 votes |

Withdrew and endorsed George Wallace: August 28, 1968 0 votes |

Assassinated: June 5, 1968 2,305,148 votes |

Withdrew: March 31, 1968 383,590 votes | |||

Enter Eugene McCarthy

Because Lyndon B. Johnson had been elected to the presidency only once, in 1964, and had served less than two full years of the term before that, the Twenty-second Amendment did not disqualify him from running for another term.[16] As a result, it was widely assumed when 1968 began that President Johnson would run for another term, and that he would have little trouble winning the Democratic nomination.

Despite growing opposition to Johnson's policies in Vietnam, it appeared that no prominent Democratic candidate would run against a sitting president of his own party. It was also accepted at the beginning of the year that Johnson's record of domestic accomplishments would overshadow public opposition to the Vietnam War and that he would easily boost his public image after he started campaigning.[17] Even Senator Robert F. Kennedy from New York, an outspoken critic of Johnson's policies, with a large base of support, publicly declined to run against Johnson in the primaries. Poll numbers also suggested that a large share of Americans who opposed the Vietnam War felt the growth of the anti-war hippie movement among younger Americans and violent unrest on college campuses was not helping their cause.[17] On January 30, however, claims by the Johnson administration that a recent troop surge would soon bring an end to the war were severely discredited when the Tet Offensive broke out. Although the American military was eventually able to fend off the attacks, and also inflict heavy losses among the communist opposition, the ability of the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong to launch large scale attacks during the Tet Offensive's long duration greatly weakened American support for the military draft and further combat operations in Vietnam.[18] A recorded phone conversation which Johnson had with Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley on January 27 revealed that both men had become aware of Kennedy's private intention to enter the Democratic presidential primaries and that Johnson was willing to accept Daley's offer to run as Humphrey's vice presidential running mate if he were to end his re-election campaign.[19] Daley, whose city would host the 1968 Democratic National Convention, also preferred either Johnson or Humphrey over any other candidate, and stated that Kennedy had met him the week before, and that he was unsuccessful in his attempt to win over Daley's support.[19]

In time, only Senator Eugene McCarthy from Minnesota proved willing to challenge Johnson openly. Running as an anti-war candidate in the New Hampshire primary, McCarthy hoped to pressure the Democrats into publicly opposing the Vietnam War. Since New Hampshire was the first presidential primary of 1968, McCarthy poured most of his limited resources into the state. He was boosted by thousands of young college students, led by youth coordinator Sam Brown,[20] who shaved their beards and cut their hair to be "Clean for Gene". These students organized get-out-the-vote drives, rang doorbells, distributed McCarthy buttons and leaflets, and worked hard in New Hampshire for McCarthy. On March 12, McCarthy won 42 percent of the primary vote, to Johnson's 49 percent, a shockingly strong showing against an incumbent president, which was even more impressive because Johnson had more than 24 supporters running for the Democratic National Convention delegate slots to be filled in the election, while McCarthy's campaign organized more strategically. McCarthy won 20 of the 24 delegates. This gave McCarthy's campaign legitimacy and momentum. Sensing Johnson's vulnerability, Senator Robert F. Kennedy announced his candidacy four days after the New Hampshire primary on March 16. Thereafter, McCarthy and Kennedy engaged in a series of state primaries.

Johnson withdraws

On March 31, 1968, following the New Hampshire primary and Kennedy's entry into the election, the president made a televised speech to the nation and said that he was suspending all bombing of North Vietnam in favor of peace talks. After concluding his speech, Johnson announced,

"With America's sons in the fields far away, with America's future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world's hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties, other than the awesome duties of this office — the presidency of your country. Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President."

Not discussed publicly at the time was Johnson's concern that he might not survive another term – Johnson's health was poor, and he had already suffered a serious heart attack in 1955.[21] He died on January 22, 1973, two days after the end of the new presidential term. Bleak political forecasts also contributed to Johnson's withdrawal; internal polling by Johnson's campaign in Wisconsin, the next state to hold a primary election, showed the President trailing badly.[22]

Historians have debated why Johnson quit a few days after his weak showing in New Hampshire. Jeff Shesol says Johnson wanted out of the White House, but also wanted vindication; when the indicators turned negative, he decided to leave.[23] Lewis L. Gould says that Johnson had neglected the Democratic party, was hurting it by his Vietnam policies, and under-estimated McCarthy's strength until the last minute, when it was too late for Johnson to recover.[24] Randall Bennett Woods said Johnson realized he needed to leave, for the nation to heal.[25] Robert Dallek writes that Johnson had no further domestic goals, and realized that his personality had eroded his popularity. His health was poor, and he was pre-occupied with the Kennedy campaign; his wife was pressing for his retirement, and his base of support continued to shrink. Leaving the race would allow him to pose as a peace-maker.[26] Anthony J. Bennett, however, said Johnson "had been forced out of a re-election race in 1968 by outrage over his policy in Southeast Asia".[27]

In 2009, an AP reporter said that Johnson decided to end his re-election bid after CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite, who was influential, turned against the president's policy in Vietnam. During a CBS News editorial which aired on February 27, Cronkite recommended the US pursue peace negotiations.[28][29] After watching Cronkite's editorial, Johnson allegedly exclaimed: "If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost Middle America."[28] This quote by Johnson has been disputed for accuracy.[30] Johnson was attending Texas Governor John Connally's birthday gala in Austin, Texas, when Cronkite's editorial aired and did not see the original broadcast.[30] But, Cronkite and CBS News correspondent Bob Schieffer defended reports that the remark had been made. They said that members of Johnson's inner circle, who had watched the editorial with the president, including presidential aide George Christian and journalist Bill Moyers, later confirmed the accuracy of the quote to them.[31][32] Schieffer, who was a reporter for the Star-Telegram's WBAP television station in Fort Worth, Texas, when Cronkite's editorial aired, acknowledged reports that the president saw the editorial's original broadcast were inaccurate,[32] but claimed the president was able to watch a taping of it the morning after it aired and then made the remark.[32] However, Johnson's January 27, 1968, phone conversion with Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley revealed that the two were trying to feed Robert Kennedy's ego so he would stay in the race, convincing him that the Democratic Party was undergoing a "revolution".[19] They suggested he might earn a spot as vice president.[19]

After Johnson's withdrawal, the Democratic Party quickly split into four factions.

- The first faction consisted of labor unions and big-city party bosses (led by Mayor Richard J. Daley). This group had traditionally controlled the Democratic Party since the days of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and they feared loss of their control over the party. After Johnson's withdrawal this group rallied to support Hubert Humphrey, Johnson's vice-president; it was also believed that President Johnson himself was covertly supporting Humphrey, despite his public claims of neutrality.

- The second faction, which rallied behind Senator Eugene McCarthy, was composed of college students, intellectuals, and upper-middle-class urban whites who had been the early activists against the war in Vietnam; they perceived themselves as the future of the Democratic Party.

- The third group was primarily composed of African Americans and Hispanic Americans, as well as some anti-war groups; these groups rallied behind Senator Robert F. Kennedy.

- The fourth group consisted of white Southern Democrats. Some older voters, remembering the New Deal's positive impact upon the rural South, supported Vice-president Humphrey. Many would rally behind the third-party campaign of former Alabama Governor George Wallace as a "law and order" candidate.

Since the Vietnam War had become the major issue that was dividing the Democratic Party, and Johnson had come to symbolize the war for many liberal Democrats, Johnson believed that he could not win the nomination without a major struggle, and that he would probably lose the election in November to the Republicans. However, by withdrawing from the race, he could avoid the stigma of defeat, and he could keep control of the party machinery by giving the nomination to Humphrey, who had been a loyal vice-president.[33] Milne (2011) argues that, in terms of foreign-policy in the Vietnam War, Johnson at the end wanted Nixon to be president rather than Humphrey, since Johnson agreed with Nixon, rather than Humphrey, on the need to defend South Vietnam from communism.[34] However, Johnson's telephone calls show that Johnson believed the Nixon camp was deliberately sabotaging the Paris peace talks. He told Humphrey, who refused to use allegations based on illegal wiretaps of a presidential candidate. Nixon himself called Johnson and denied the allegations. Dallek concludes that Nixon's advice to Saigon made no difference, and that Humphrey was so closely identified with Johnson's unpopular policies that no last-minute deal with Hanoi could have affected the election.[35]

Contest

After Johnson's withdrawal, Vice President Hubert Humphrey announced his candidacy. Kennedy was successful in four state primaries (Indiana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and California), and McCarthy won six (Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Oregon, New Jersey, and Illinois). However, in primaries where they campaigned directly against one another, Kennedy won four primaries (Indiana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and California), and McCarthy won only one (Oregon).[36] Humphrey did not compete in the primaries, leaving that job to favorite sons who were his surrogates, notably United States Senator George A. Smathers from Florida, United States Senator Stephen M. Young from Ohio, and Governor Roger D. Branigin of Indiana. Instead, Humphrey concentrated on winning the delegates in non-primary states, where party leaders such as Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley controlled the delegate votes in their states. Kennedy defeated Branigin and McCarthy in the Indiana primary on May 7, and then defeated McCarthy in the Nebraska primary on May 14. However, McCarthy upset Kennedy in the Oregon primary on May 28.

After Kennedy's defeat in Oregon, the California primary was seen as crucial to both Kennedy and McCarthy. McCarthy stumped the state's many colleges and universities, where he was treated as a hero for being the first presidential candidate to oppose the war. Kennedy campaigned in the ghettos and barrios of the state's larger cities, where he was mobbed by enthusiastic supporters. Kennedy and McCarthy engaged in a television debate a few days before the primary; it was generally considered a draw. On June 4, Kennedy narrowly defeated McCarthy in California, 46%–42%. However, McCarthy refused to withdraw from the race, and made it clear that he would contest Kennedy in the upcoming New York primary on June 18, where McCarthy had much support from anti-war activists. In the early morning of June 5, after giving his victory speech in Los Angeles, Kennedy was assassinated by Sirhan Sirhan, a 24-year-old Palestinian-Jordanian. Kennedy died 26 hours later at Good Samaritan Hospital. Sirhan admitted his guilt, was convicted of murder, and is still in prison.[37] In recent years some have cast doubt on Sirhan's guilt, including Sirhan himself, who said he was "brainwashed" into killing Kennedy and was a patsy.[38]

Political historians still debate whether Kennedy could have won the Democratic nomination, had he lived. Some historians, such as Theodore H. White and Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., have argued that Kennedy's broad appeal and famed charisma would have convinced the party bosses at the Democratic Convention to give him the nomination.[39] Jack Newfield, author of RFK: A Memoir, stated in a 1998 interview that on the night he was assassinated, "[Kennedy] had a phone conversation with Mayor Daley of Chicago, and Mayor Daley all but promised to throw the Illinois delegates to Bobby at the convention in August 1968. I think he said to me, and Pete Hamill: 'Daley is the ball game, and I think we have Daley.'"[40] However, other writers such as Tom Wicker, who covered the Kennedy campaign for The New York Times, believe that Humphrey's large lead in delegate votes from non-primary states, combined with Senator McCarthy's refusal to quit the race, would have prevented Kennedy from ever winning a majority at the Democratic Convention, and that Humphrey would have been the Democratic nominee, even if Kennedy had lived.[41] The journalist Richard Reeves and historian Michael Beschloss have both written that Humphrey was the likely nominee,[42] and future Democratic National Committee chairman Larry O'Brien wrote in his memoirs that Kennedy's chances of winning the nomination had been slim, even after his win in California.[43]

At the moment of RFK's death, the delegate totals were:

- Hubert Humphrey – 561

- Robert F. Kennedy – 393

- Eugene McCarthy – 258

Total popular vote:[44]

|

|

Democratic Convention and antiwar protests

Robert Kennedy's death altered the dynamics of the race. Although Humphrey appeared the presumptive favorite for the nomination, thanks to his support from the traditional power blocs of the party, he was an unpopular choice with many of the anti-war elements within the party, who identified him with Johnson's controversial position on the Vietnam War. However, Kennedy's delegates failed to unite behind a single candidate who could have prevented Humphrey from getting the nomination. Some of Kennedy's support went to McCarthy, but many of Kennedy's delegates, remembering their bitter primary battles with McCarthy, refused to vote for him. Instead, these delegates rallied around the late-starting candidacy of Senator George McGovern of South Dakota, a Kennedy supporter in the spring primaries who had presidential ambitions himself. This division of the anti-war votes at the Democratic Convention made it easier for Humphrey to gather the delegates he needed to win the nomination.

When the 1968 Democratic National Convention opened in Chicago, thousands of young activists from around the nation gathered in the city to protest the Vietnam War. On the evening of August 28, in a clash which was covered on live television, Americans were shocked to see Chicago police brutally beating anti-war protesters in the streets of Chicago in front of the Conrad Hilton Hotel. While the protesters chanted, "The whole world is watching", the police used clubs and tear gas to beat back or arrest the protesters, leaving many of them bloody and dazed. The tear gas wafted into numerous hotel suites; in one of them Vice President Humphrey was watching the proceedings on television. The police said that their actions were justified because numerous police officers were being injured by bottles, rocks, and broken glass that were being thrown at them by the protestors. The protestors had also yelled insults at the police, calling them "pigs" and other epithets. The anti-war and police riot divided the Democratic Party's base: some supported the protestors and felt that the police were being heavy-handed, but others disapproved of the violence and supported the police. Meanwhile, the convention itself was marred by the strong-arm tactics of Chicago's mayor Richard J. Daley (who was seen on television angrily cursing Senator Abraham Ribicoff from Connecticut, who made a speech at the convention denouncing the excesses of the Chicago police). In the end, the nomination itself was anticlimactic, with Vice-president Humphrey handily beating McCarthy and McGovern on the first ballot.

After the delegates nominated Humphrey, the convention then turned to selecting a vice-presidential nominee. The main candidates for this position were Senators Edward M. Kennedy from Massachusetts, Edmund Muskie from Maine, and Fred R. Harris from Oklahoma; Governors Richard Hughes of New Jersey and Terry Sanford of North Carolina; Mayor Joseph Alioto of San Francisco, California; former Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance; and Ambassador Sargent Shriver from Maryland. Another idea floated was to tap Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, one of the most liberal Republicans. Ted Kennedy was Humphrey's first choice, but the senator turned him down. After narrowing it down to Senator Muskie and Senator Harris, Vice-president Humphrey chose Muskie, a moderate and environmentalist from Maine, for the nomination. The convention complied with the request and nominated Senator Muskie as Humphrey's running mate.

The publicity from the anti-war riots crippled Humphrey's campaign from the start, and it never fully recovered. Before 1968 the city of Chicago had been a frequent host for the political conventions of both parties; since 1968 only two national conventions have been held there: the Democratic convention of 1996, which nominated Bill Clinton for a second term, and the Democratic convention of 2024, which nominated Kamala Harris.[45]

| Presidential tally | Vice Presidential tally | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hubert Humphrey | 1759.25 | Edmund S. Muskie | 1942.5 |

| Eugene McCarthy | 601 | Not Voting | 604.25 |

| George S. McGovern | 146.5 | Julian Bond | 48.5 |

| Channing Phillips | 67.5 | David Hoeh | 4 |

| Daniel K. Moore | 17.5 | Edward M. Kennedy | 3.5 |

| Edward M. Kennedy | 12.75 | Eugene McCarthy | 3.0 |

| Paul W. "Bear" Bryant | 1.5 | Others | 16.25 |

| James H. Gray | 0.5 | ||

| George Wallace | 0.5 | ||

Source: Keating Holland, "All the Votes... Really", CNN[46]

Endorsements

Hubert Humphrey

- President Lyndon B. Johnson

- Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago

- Former President Harry S. Truman

- Singer/actor Frank Sinatra

Robert F. Kennedy

- Senator Abraham Ribicoff from Connecticut[47]

- Senator George McGovern from South Dakota[48]

- Senator Vance Hartke from Indiana[49]

- Labor Leader Cesar Chavez

- Writer Truman Capote[50]

- Writer Norman Mailer

- Actress Shirley MacLaine[50]

- Actress Stefanie Powers

- Actor Robert Vaughn

- Actor Peter Lawford

- Singer Bobby Darin[51]

Eugene McCarthy

- Representative Don Edwards from California

- Actor Paul Newman

- Actress Tallulah Bankhead[50]

- Playwright Arthur Miller[50]

- Writer William Styron[50]

George McGovern (during convention)

- Senator Abraham Ribicoff from Connecticut

- Governor Harold E. Hughes of Iowa

American Independent Party nomination

|

1968 American Independent Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| George Wallace | Curtis LeMay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45th Governor of Alabama (1963–1967) |

Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force (1961–1965) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The American Independent Party, which was established in 1967 by Bill and Eileen Shearer, nominated former Alabama Governor George Wallace – whose pro-racial segregation policies had been rejected by the mainstream of the Democratic Party – as the party's candidate for president. The impact of the Wallace campaign was substantial, winning the electoral votes of several states in the Deep South. He appeared on the ballot in all fifty states, but not the District of Columbia. Although he did not come close to winning any states outside the South, Wallace was the 1968 presidential candidate who most disproportionately drew his support from among young men.[52] Wallace also proved to be popular among blue-collar workers in the North and Midwest, and he took many votes which might have gone to Humphrey.[53]

Wallace was not expected to win the election – his strategy was to prevent either major party candidate from winning a preliminary majority in the Electoral College. Although Wallace put considerable effort into mounting a serious general election campaign, his presidential bid was also a continuation of Southern efforts to elect unpledged electors that had taken place in every election from 1956 – he had his electors promise to vote not necessarily for him but rather for whomever he directed them to support – his objective was not to move the election into the U.S. House of Representatives where he would have had little influence, but rather to give himself the bargaining power to determine the winner. Wallace's running mate was retired four star General Curtis LeMay.

Prior to deciding on LeMay, Wallace gave serious consideration to former U.S. senator, governor, and Baseball Commissioner A. B. Happy Chandler of Kentucky as his running mate.[54] Chandler and Wallace met a number of times; however, Chandler said that he and Wallace were unable to come to an agreement regarding their positions on racial matters. Chandler had supported the segregationist Dixiecrats in the 1948 presidential elections. However, after being re-elected Governor of Kentucky in 1955, he used National Guard troops to enforce school integration.[55] Other considerations included ABC newscaster Paul Harvey of Oklahoma, former Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson of Utah, former Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus, and even Kentucky Fried Chicken founder Colonel Sanders.[56]

Wallace's position of withdrawing from Vietnam if the war was "not winnable within 90 days"[57] was overshadowed by LeMay, implying he would use nuclear weapons to win the war.[58]

Other parties and candidates

Also on the ballot in two or more states were black activist Eldridge Cleaver (who was ineligible to take office, as he would have only been 33 years of age on January 20, 1969) for the Peace and Freedom Party; Henning Blomen for the Socialist Labor Party; Fred Halstead for the Socialist Workers Party; E. Harold Munn for the Prohibition Party; and Charlene Mitchell – the first African-American woman to run for president, and the first woman to receive valid votes in a general election – for the Communist Party. Comedians Dick Gregory and Pat Paulsen were notable write-in candidates. A facetious presidential candidate for 1968 was a pig named Pigasus, as a political statement by the Yippies, to illustrate their premise that "one pig's as good as any other".[59][page needed]

General election

Polling

<graph>{"legends":[],"scales":[{"type":"time","name":"x","domain":{"data":"chart","field":"x"},"range":"width","zero":false},{"type":"linear","name":"y","domain":{"data":"chart","field":"y"},"zero":false,"range":"height","nice":true},{"domain":{"data":"chart","field":"series"},"type":"ordinal","name":"color","range":["#e81b23","#3333ff","#ff7f00","silver","#e81b23","#3333ff","#ff7f00","lightsteelblue","#808080"]},{"domain":{"data":"chart","field":"series"},"type":"ordinal","name":"symSize","range":[0,0,0,0,76.5,76.5,76.5,76.5]}],"version":2,"marks":[{"type":"group","marks":[{"properties":{"hover":{"stroke":{"value":"red"}},"update":{"stroke":{"scale":"color","field":"series"}},"enter":{"y":{"scale":"y","field":"y"},"x":{"scale":"x","field":"x"},"stroke":{"scale":"color","field":"series"},"interpolate":{"value":"basis"},"strokeWidth":{"value":2}}},"type":"line"},{"properties":{"enter":{"y":{"scale":"y","field":"y"},"x":{"scale":"x","field":"x"},"size":{"scale":"symSize","field":"series"},"fill":{"scale":"color","field":"series"},"stroke":{"scale":"color","field":"series"},"shape":{"value":"circle"},"strokeWidth":{"value":0}}},"type":"symbol"}],"from":{"data":"chart","transform":[{"groupby":["series"],"type":"facet"}]}},{"type":"rule","properties":{"update":{"y":{"value":0},"x":{"scale":"x","field":"x"},"opacity":{"value":0.75},"y2":{"field":{"group":"height"}},"stroke":{"value":"#54595d"},"strokeWidth":{"value":"#54595d"}}},"from":{"data":"v_anno"}},{"type":"text","properties":{"update":{"y":{"offset":-3,"field":{"group":"height"}},"x":{"scale":"x","offset":3,"field":"x"},"opacity":{"value":0.75},"baseline":{"value":"top"},"text":{"field":"label"},"angle":{"value":-90},"fill":{"value":"#54595d"}}},"from":{"data":"v_anno"}}],"height":450,"axes":[{"type":"x","scale":"x","properties":{"title":{"fill":{"value":"#54595d"}},"grid":{"stroke":{"value":"#54595d"}},"ticks":{"stroke":{"value":"#54595d"}},"axis":{"strokeWidth":{"value":2},"stroke":{"value":"#54595d"}},"labels":{"align":{"value":"right"},"angle":{"value":-40},"fill":{"value":"#54595d"}}},"grid":false},{"type":"y","title":"% Support","scale":"y","properties":{"title":{"fill":{"value":"#54595d"}},"grid":{"stroke":{"value":"#54595d"}},"ticks":{"stroke":{"value":"#54595d"}},"axis":{"strokeWidth":{"value":2},"stroke":{"value":"#54595d"}},"labels":{"fill":{"value":"#54595d"}}},"grid":true}],"data":[{"format":{"parse":{"y":"number","x":"date"},"type":"json"},"name":"chart","values":[{"y":34,"series":"y1","x":"1968/04/06"},{"y":43,"series":"y1","x":"1968/04/26"},{"y":36,"series":"y1","x":"1968/05/06"},{"y":39,"series":"y1","x":"1968/05/12"},{"y":37,"series":"y1","x":"1968/05/23"},{"y":36,"series":"y1","x":"1968/06/12"},{"y":37,"series":"y1","x":"1968/06/23"},{"y":35,"series":"y1","x":"1968/07/11"},{"y":35,"series":"y1","x":"1968/07/20"},{"y":40,"series":"y1","x":"1968/07/31"},{"y":45,"series":"y1","x":"1968/08/21"},{"y":40,"series":"y1","x":"1968/08/27"},{"y":43,"series":"y1","x":"1968/09/11"},{"y":39,"series":"y1","x":"1968/09/23"},{"y":43,"series":"y1","x":"1968/09/29"},{"y":44,"series":"y1","x":"1968/10/10"},{"y":40,"series":"y1","x":"1968/10/18"},{"y":44,"series":"y1","x":"1968/10/24"},{"y":40,"series":"y1","x":"1968/11/01"},{"y":42,"series":"y1","x":"1968/11/04"},{"y":35,"series":"y2","x":"1968/04/06"},{"y":34,"series":"y2","x":"1968/04/26"},{"y":38,"series":"y2","x":"1968/05/06"},{"y":36,"series":"y2","x":"1968/05/12"},{"y":41,"series":"y2","x":"1968/05/23"},{"y":42,"series":"y2","x":"1968/06/12"},{"y":42,"series":"y2","x":"1968/06/23"},{"y":40,"series":"y2","x":"1968/07/11"},{"y":37,"series":"y2","x":"1968/07/20"},{"y":38,"series":"y2","x":"1968/07/31"},{"y":29,"series":"y2","x":"1968/08/21"},{"y":34,"series":"y2","x":"1968/08/27"},{"y":31,"series":"y2","x":"1968/09/11"},{"y":31,"series":"y2","x":"1968/09/23"},{"y":28,"series":"y2","x":"1968/09/29"},{"y":29,"series":"y2","x":"1968/10/10"},{"y":35,"series":"y2","x":"1968/10/18"},{"y":36,"series":"y2","x":"1968/10/24"},{"y":37,"series":"y2","x":"1968/11/01"},{"y":40,"series":"y2","x":"1968/11/04"},{"y":12,"series":"y3","x":"1968/04/06"},{"y":14,"series":"y3","x":"1968/04/26"},{"y":13,"series":"y3","x":"1968/05/06"},{"y":14,"series":"y3","x":"1968/05/12"},{"y":14,"series":"y3","x":"1968/05/23"},{"y":14,"series":"y3","x":"1968/06/12"},{"y":14,"series":"y3","x":"1968/06/23"},{"y":16,"series":"y3","x":"1968/07/11"},{"y":17,"series":"y3","x":"1968/07/20"},{"y":16,"series":"y3","x":"1968/07/31"},{"y":18,"series":"y3","x":"1968/08/21"},{"y":17,"series":"y3","x":"1968/08/27"},{"y":19,"series":"y3","x":"1968/09/11"},{"y":21,"series":"y3","x":"1968/09/23"},{"y":21,"series":"y3","x":"1968/09/29"},{"y":20,"series":"y3","x":"1968/10/10"},{"y":18,"series":"y3","x":"1968/10/18"},{"y":15,"series":"y3","x":"1968/10/24"},{"y":16,"series":"y3","x":"1968/11/01"},{"y":14,"series":"y3","x":"1968/11/04"},{"y":19,"series":"y4","x":"1968/04/06"},{"y":9,"series":"y4","x":"1968/04/26"},{"y":13,"series":"y4","x":"1968/05/06"},{"y":11,"series":"y4","x":"1968/05/12"},{"y":8,"series":"y4","x":"1968/05/23"},{"y":8,"series":"y4","x":"1968/06/12"},{"y":7,"series":"y4","x":"1968/06/23"},{"y":9,"series":"y4","x":"1968/07/11"},{"y":11,"series":"y4","x":"1968/07/20"},{"y":6,"series":"y4","x":"1968/07/31"},{"y":8,"series":"y4","x":"1968/08/21"},{"y":9,"series":"y4","x":"1968/08/27"},{"y":7,"series":"y4","x":"1968/09/11"},{"y":9,"series":"y4","x":"1968/09/23"},{"y":8,"series":"y4","x":"1968/09/29"},{"y":7,"series":"y4","x":"1968/10/10"},{"y":7,"series":"y4","x":"1968/10/18"},{"y":5,"series":"y4","x":"1968/10/24"},{"y":7,"series":"y4","x":"1968/11/01"},{"y":7,"series":"y4","x":"1968/11/04"},{"y":43.42,"series":"y5","x":"1968/11/05"},{"y":42.72,"series":"y6","x":"1968/11/05"},{"y":13.53,"series":"y7","x":"1968/11/05"},{"y":0.33,"series":"y8","x":"1968/11/05"}]},{"format":{"parse":{"x":"date"},"type":"json"},"name":"v_anno","values":[{"label":"Republican National Convention","x":"1968/08/05"},{"label":"Democratic National Convention","x":"1968/08/25"}]}],"width":950}</graph>

| Poll source | Date | Richard Nixon Republican |

Hubert Humphrey Democratic |

George Wallace American Ind. |

Undecided/Other | Leading by (points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election Results | November 5, 1968 | 43.42% | 42.72% | 13.53% | 0.33% | 0.70 |

| Harris[60] | November 4, 1968 | 40% | 43% | 13% | 4% | 3 |

| Gallup[61] | November 4, 1968 | 42% | 40% | 14% | 4% | 2 |

| Harris[62] | November 1, 1968 | 40% | 37% | 16% | 7% | 3 |

| Gallup[63] | October 24, 1968 | 44% | 36% | 15% | 5% | 8 |

| Harris[64] | October 18, 1968 | 40% | 35% | 18% | 7% | 5 |

| Gallup[65] | October 9, 1968 | 44% | 29% | 20% | 7% | 8 |

| Gallup[66] | September 29, 1968 | 43% | 28% | 21% | 8% | 15 |

| Harris[67] | September 23, 1968 | 39% | 31% | 21% | 9% | 8 |

| Gallup[68] | September 11, 1968 | 43% | 31% | 19% | 7% | 12 |

| Harris[69] | August 27, 1968 | 40% | 34% | 17% | 9% | 6 |

| Gallup[70] | August 21, 1968 | 45% | 29% | 18% | 8% | 16 |

| Harris[71][72] | July 31, 1968 | 36% | 41% | 16% | 7% | 5 |

| Crossley[71][73] | July 31, 1968 | 39% | 36% | 19% | 6% | 3 |

| Gallup[74] | July 31, 1968 | 40% | 38% | 16% | 6% | 2 |

| Harris[75][69] | July 20, 1968 | 35% | 37% | 17% | 11% | 2 |

| Gallup[76] | July 11, 1968 | 35% | 40% | 16% | 9% | 5 |

| Harris[77] | June 24, 1968 | - | - | - | - | 7 |

| Gallup[78] | June 23, 1968 | 37% | 42% | 14% | 7% | 5 |

| Gallup[79] | June 12, 1968 | 36% | 42% | 14% | 8% | 6 |

| Harris[80] | May 23, 1968 | 37% | 41% | 14% | 8% | 4 |

| Gallup[81] | May 12, 1968 | 39% | 36% | 14% | 11% | 3 |

| Harris[82] | May 6, 1968 | 36% | 38% | 13% | 13% | 2 |

| Gallup[83] | April 21, 1968 | 43% | 34% | 14% | 9% | 9 |

| Harris[84] | April 6, 1968 | 34% | 35% | 12% | 19% | 1 |

Campaign strategies

Nixon developed a "Southern strategy" that was designed to appeal to conservative white southerners, who had traditionally voted Democratic, but were opposed to Johnson and Humphrey's support for the civil rights movement, as well as the rioting that had broken out in most large cities. Wallace, however, won over many of the voters Nixon targeted, effectively splitting that voting bloc. Wallace deliberately targeted many states he had little chance of carrying himself in the hope that by splitting as many votes with Nixon as possible he would give competitive states to Humphrey and, by extension, boost his own chances of denying both opponents an Electoral College majority.[85]

Since he was well behind Nixon in the polls as the campaign began, Humphrey opted for a slashing, fighting campaign style. He repeatedly – and unsuccessfully – challenged Nixon to a televised debate, and he often compared his campaign to the successful underdog effort of President Harry Truman, another Democrat who had trailed in the polls, in the 1948 presidential election. Humphrey predicted that he, like Truman, would surprise the experts and win an upset victory.[86]

Campaign themes

Nixon campaigned on a theme to restore "law and order",[87] which appealed to many voters angry with the hundreds of violent riots that had taken place across the country in the previous few years. Following the murder of Martin Luther King in April 1968, there was massive rioting in inner city areas. The police were overwhelmed and President Johnson decided to call out the U.S. Army. Nixon also opposed forced busing to desegregate schools.[88] Proclaiming himself a supporter of civil rights, he recommended education as the solution rather than militancy. During the campaign, Nixon proposed government tax incentives to African Americans for small businesses and home improvements in their existing neighborhoods.[89]

During the campaign, Nixon also used as a theme his opposition to the decisions of Chief Justice Earl Warren, pledging to "remake the Supreme Court."[90] Many conservatives were critical of Chief Justice Warren for using the Supreme Court to promote liberal policies in the fields of civil rights, civil liberties, and the separation of church and state. Nixon promised that if he were elected president, he would appoint justices who would take a less-active role in creating social policy.[91] In another campaign promise, he pledged to end the draft.[92] During the 1960s, Nixon had been impressed by a paper he had read by Professor Martin Anderson of Columbia University. Anderson had argued in the paper for an end to the draft and the creation of an all-volunteer army.[93] Nixon also saw ending the draft as an effective way to undermine the anti-Vietnam war movement, since he believed affluent college-age youths would stop protesting the war once their own possibility of having to fight in it was gone.[94]

Humphrey, meanwhile, promised to continue and expand the Great Society welfare programs started by President Johnson, and to continue the Johnson Administration's "War on poverty". He also promised to continue the efforts of presidents Kennedy and Johnson, and the Supreme Court, in promoting the expansion of civil rights and civil liberties for minority groups. However, Humphrey also felt constrained for most of his campaign in voicing any opposition to the Vietnam War policies of President Johnson, due to his fear that Johnson would reject any peace proposals he made and undermine his campaign. As a result, early in his campaign Humphrey often found himself the target of anti-war protestors, some of whom heckled and disrupted his campaign rallies.

Humphrey's comeback and the October surprise